Are They Collaborators?

John Haberin New York City

Robert Frank: Films, Collaborations, and Contact Sheets

Are These Men Collaborators? It was 1983, and Joan Lyons posed the question in her title to a print. Robert Frank, among those posing for the camera, must have wondered as well. Among the greatest American photographers ever, was he fated to go it alone?

He must have wondered how much it was worth collaborating from the moment he arrived in New York in 1947, as a Jew from Switzerland. Not even a neutral nation could protect his family and community from the Nazis. He found work almost instantly, in fashion photography, first for Harper's Bazaar—but was that itself a collaboration, with editors and professional models, or just a reminder of everything he mistrusted about America?  He left almost as quickly for the road, for what became The Americans in 1958. It gave a face to Americans like no other work in photography, but were they, too, collaborators, or was he that much more in exile? Viewers ever since have wondered if this was their America, too.

He left almost as quickly for the road, for what became The Americans in 1958. It gave a face to Americans like no other work in photography, but were they, too, collaborators, or was he that much more in exile? Viewers ever since have wondered if this was their America, too.

Now MoMA picks up the story, with photography and film from the rest of his life, while a gallery sticks to his contact sheets. The museum follows him through two marriages, both to artists, and to New York in the excitement of Beat poetry and abstract art—and with an emphasis on collaboration every step of the way. It takes him and his family to Nova Scotia, where he moved part time in 1970. He loved not just sky and sea, but even more his new neighbors. By his death in 2019, his circle had shrunk, as he spent more and more time not just in Cape Breton, but in his house alone. MoMA sees a turn after The Americans to work with others, but its poignancy may lie instead in how much he had to leave behind. Still, as the show's title has it, "Life Dances On."

Restless Americans

That photograph of, just maybe, collaborators, should tell you something. They have been hanging out a long time now, and no one would dream of telling them how to pose. Still, one appears behind the rest, on-screen or in a print, eager to join them but not altogether there. A couple hugs, but Frank stands apart at far right. He looks older as well, just short of sixty, with white hair and a scraggly beard. Hand-lettered labels below each person make them look like perps in police custody.

Frank was always restless. He had to hit the road for The Americans, and it testifies to a restless America. I caught up with him at the Met in 2010—and do check out my review then, which I would not dream of repeating. The series makes the perfect contrast to "America by Car" by Lee Friedlander, for no one had his feet on the ground as much as Frank. He stuck to the people he met and the symbols they embrace, in unsettled compositions. He was not going to wait around for photography's "decisive moment."

The book itself remained unsettled until practically the day of publication (in 1957 in Paris). Frank kept returning to his contact prints, circling and changing his choices. MoMA has it right when it includes contact prints among other discoveries, and it salvages film that he never released, too, as "scrapbook footage" in the basement theater. It boasts of its truth to Frank's intentions by showing them in their entirety, but that has it wrong. He made his selections. He just kept changing his mind.

Born in 1924, he left Switzerland as a restless young man, and he could not sit still on his return to New York after The Americans. Sure, he could find a seat on the bus, but only to cross the city much as he had crossed the country—and to observe what he could from a window. From the Bus opens the show at MoMA, and it can be hard to know who on the street has made a decisive, theatrical turn and who has momentarily lost his way. Frank heads downtown soon after to what he could call home, east of the Village. He casts himself in a postwar scene that is giving America its integrity and its life. He still takes on commercial work, and MoMA includes a page from Mademoiselle, but with the freedom to say no.

He photographs artists, an incredibly young James Baldwin, and Allen Ginsberg, all of them friends. He could see Willem de Kooning at work from out his window, but he would rather photograph him up close. He spends an extended period with the Rolling Stones for what became his best-known group portrait. Naturally it is the period of Exile on Main Street. Still, he shies away from telling a story about psychology, creativity, and exile. He shoots painters without a brush in hand, Baldwin and Ginsberg without a typewriter.

Nor is he making a political statement. He has room even for a conservative icon, William F. Buckley. He must have known his own conflicting feelings about America. He had to keep moving, but he distrusted his adopted country's restless spirit. To him it was the spirit of capitalism. It was time he refused to play the lone genius—a time for collaboration.

A dusty square of light

Frank photographs his friends at ease together. Others turn their camera on him, like Joan Lyons and Danny Lyon. His most obvious collaborations, though, were on films, starting in 1959 with Pull My Daisy He conceived it together with Alfred Leslie, with a script by Jack Kerouac, the author of On the Road. (Kerouac also supplies the voice-over narration.) It works through their shared ambivalence about their own creative past, with (as I put it in another past review), an undercurrent of humor and disturbance that art cannot resolve. It also moves between images of family life and the arts.

Some have found it formless, which misses its narrative, but also misses the point. It celebrates the lives of artists, including their spiritual life, but art that makes things up on the spot on the spot. And if it still seems formless, just wait till you see Frank's other films. (MoMA gives them monitors rather than rooms to themselves.) Just wait, too, till you see the rest of his photography. He pops over to Coney Island for a shoot, but this will be one long roller-coaster of a ride.

Some have found it formless, which misses its narrative, but also misses the point. It celebrates the lives of artists, including their spiritual life, but art that makes things up on the spot on the spot. And if it still seems formless, just wait till you see Frank's other films. (MoMA gives them monitors rather than rooms to themselves.) Just wait, too, till you see the rest of his photography. He pops over to Coney Island for a shoot, but this will be one long roller-coaster of a ride.

His most persistent collaborator was his second wife, June Leaf, and their greatest collaboration their move from New York. They observe much the same scenes at Cape Breton, Frank in photography and Leaf on paper. She gives acrylic and ink the translucency of watercolor—to capture the light, but also to preserve in paint the spontaneity of drawing. She renders a hand, too, perhaps Frank's own mark. They turn their thoughts most, though, to the space of a home. In years ahead, light can still penetrate, but little else.

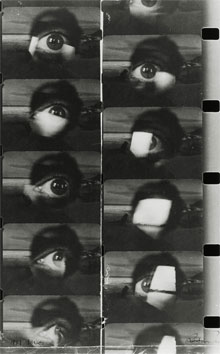

They differ in one thing: where Leaf's scenes are otherwise empty, Frank is still asking his neighbors how they live. He seems happy to have discovered Mabou, a small town on the Cape where he can know pretty much everyone. They and their homes look ramshackle and improvised. One seems to be sinking halfway into the sea. A Mabou Winter is just a half-covered eye.

Walker Evans, long a friend and advisor, stops by to take a look around. For MoMA, it is just one more sign of collaboration. Even fans have mostly given up on Frank after The Americans, and the curators, Joshua Siegel and Lucy Gallon, hope to change that. Something, though, has changed for good. There is no getting around that images become closer and closer to throwaways, much like the "scrapbook." Still, Frank knew the pain of throwing things away.

What remains is a portrait of loss. His two children died young, his daughter very young, and he himself retreats further and further within. He had always worked on the cheap, but now he trades his Leica for Polaroids—as he put it, "to strengthen the feeling." Life Dances On . . ., the 1980 print that lends the show its title, seems more and more a bitter hope. Leaf's absences of life become prophetic, and a typewriter rests untouched. An interior becomes bare walls and a dusty square of light.

The decisive contact sheet

A politician boasting of his presence and his art of manipulating a crowd, even as a face beneath him breaks down in tears? It took shot after shot for the man to raise his arms to their full extent and for the stone carving of a woman's head to emerge into the light. Those people in a trolley car? It took shot after shot for the trolley to reach that unsettling angle smack against the picture plane—and for the people to come out of the shadows to engage not each other, but rather the nation and the viewer.

When the Met exhibited The Americans in 2010, it showed Robert Frank's vision of diversity and discontent as his book developed over three trips across country and eighty-three photos. Yet it also included several outtakes, and it stressed that he ran through well over a hundred rolls of film and thousands of frames. And then in 2017 a gallery exhibits thirty-three contact sheets, out of an incredible eighty-one in a box set. It insists, too, on their completeness and Frank's complicity. It describes how the set grew from a Japanese man's dedication. He and the photographer got along just great, you see, and reached full understanding, although neither knew a word of the other's language.

It sounds like a parody or a scam, in the interest of multiples for sale, but never mind. It hardly mentions the photographs themselves or Frank's working methods, but you can gain a fresh sense of them all the same. Maybe you imagined him waiting patiently for that decisive moment or even staging the scene, in what a museum has called "Time Management." Instead, you can see him choosing a subject and snapping away. You can feel his satisfaction in circling the frame that he wants in red—or showing his indecision with a question mark. Only rarely does he have to draw the circle closer, with every intent to crop the print later on to make it more decisive.

The Americans stands for a decisive moment in history as well. The very ideal of the decisive moment goes back to Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris, to preserve its perfection once and for all. Frank came later, but also before the discontent with the past of the 1960s or the American crossings of "But Still, It Turns" today. He comes, too, between the documentary assurance of Walker Evans or Alfred Eisenstaedt and the anxiety of Diane Arbus on the dark side of New York City or Garry Winogrand and Jeff Brouws on the dark side of a nation. As I wrote much better back in 2010, the Swiss photographer was after his own engagement with America. Even more than for Lyon, photography here is both personal and political.

Frank seems determined to avoid the headlines, even while making people and politics inescapable. For all the turmoil, he is out for human contact and a record of human agency. On Flag Day, he goes for the flag on the walls of a building, but he finds that one shot in which people appear disturbingly cut off in the windows. At a Fourth of July picnic, he finds that shot in which people neither hang out aimlessly on the one hand nor march in lockstep on the other, but rather stride. At a campaign rally for Adlai Stevenson, he finds that shot with not a trace of a banner—to capture instead a lone person with a sign and a message. To subordinate his subjects to someone else's order just will not do, not even Stevenson's on the left.

Did he even know where he was going apart from them? I can imagine him either circling the print he always wanted or coming upon it with as much surprise as yours or mine today. He spots that one shot at a drive-in with a clear image of the screen and a competing point of artificial light, with people implicit in the darkness. He spots, too, a dark car at the vanishing point of a highway flooded with reflected light. Early critics saw people going nowhere, and they saw the slack faces and seemingly casual compositions as an affront to America or to art. Yet even the appearance of disorder required a decisive moment.

Robert Frank ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 11, 2025, and at Danziger through April 8, 2017. A related review looks at Frank's "The Americans."